About the authors

It was in 1987 that my good friend Pieter Keijzer and I, Sarah de Monchy, decided together to take a dog, ending up with both having a Samoyed puppy, two males of the same litter. Neither of us had experienced a Samoyed before. We selected this breed, as we wanted a dog that was friendly to strangers and fit to accompany us when camping and hiking in the mountains. So it had to be a good walker, protected by an all-weather coat. These little white bears developed into beautiful wolfish dogs, easy to take everywhere, great company on winter and summer holidays and a feast for the eye when playing with each other or running and hunting through fields and woods, now and then checking in with me, their eyes shining of sheer joy in live.

Today, I share my live with two sons of the last litter sired by one of these two dogs. Now, as the second generation I owe has turned seven years old, and if reaching the same age as their father, I will be enjoying their company for seven more years to come. But the looks of these dogs, that have become so familiar to me, appear to be getting pretty rare. And I have become more and more aware of the fact that the chances for obtaining such dogs ever again, are diminishing every day.

Through the years the interest in the breed grew with both of us. In Pieter’s case, it became a hobby to find out more about the background of the breed, triggered by the dive he took in the library of the University of Amsterdam, in search for Samoyedic names for the pups. The fruit of several years reading and collecting books, articles and pictures of early Samoyeds is now gradually to be found on the website on the history of the Samoyed dog that he is building.

Part I: A short history of the Samoyed dog in its

home country (by Pieter Keijzer © 2005)

1. The Samoyed peoples

Introduction

To write a history of the Samoyed dog one has to consider that the live and tasks of the aboriginal Samoyed dogs, the dogs living with the Samoyed peoples, differ considerably with that of the Samoyed dogs now living in the Western civilized world. The modern Samoyed dogs have, thanks to the ever increasing demand to score on dog shows, even undergone a considerable change in exterior compared to the aboriginal Samoyed dogs.

The Samoyed dog is originally an all white dog with long standing fur and a vivid and athletic appearance. The name of this breed is derived from the Samoyedic speaking peoples living on the tundra’s and in the taiga’s of Northern European Russia and North-west Siberia, globally stretching from the White Sea in the West to the Taymir Peninsula in Siberia. As the history of aboriginal dogs is linked with that of the peoples - as Vladimir Beregovoy already pointed out in his article in the first issue of R-PADS newsletter - we must, in order to be able to sketch a background picture, turn our attention a little towards the Samoyed peoples first.

Language and culture

The Samoyeds are not one people but a group of peoples speaking Samoyed languages, languages that are distantly related to the Finno-Ugrian languages, such as Finnish, Hungarian, Komi, Permian Khanty, Mansi and other languages.

Both the Samoyed and Finno-Ugrian languages belong to the Uralic language group, the Uralians being the far forefathers of the peoples speaking these languages. These Uralians are thought to have lived in what is now called European Russia, near the Ural Mountains. The Samoyed language group now encompasses the languages of the Nenets, Enets, Sel’kup and Nganasan, the latter being the northernmost living peoples of the world. All of these names refer to our word for ‘Man’.

The Nenets are the most numeral of the Samoyed peoples, numbering about 30.000 people. The smallest group of Samoyeds are the Enets, numbering 209 Enets speaking people counted in 1989 and listed as endangered peoples beyond the point of no return. More Samoyed peoples, like the Kamasin, Motor etc., have existed but are now extinct. One of them as recently as 1919, when the last Kamasin died. Although already in the 17th century the Englishman Peter Mundy and the Dutchman Nicolaes Witsen had published several Nenets words, a real study of the languages was only published in the 1820’s by the Finnish linguist Mattias Alexander Castrén.

At the time of the first imports of Samoyed dogs (the last decennium of the 19th century) the Nenets were living in the broad area from the White Sea in the West to the mouth of the Yenissei river in the East. The Enets were then living on the Eastern shores of the Yenissei river from about Golchika in the North down toward the town of Turuchansk. The Nganasans lived (and still live) on the Taimyr Peninsula. Another part of the Samoyeds remained living in Southern Siberia and the Sayan mountains. Their languages, most of them extinct nowadays, are called the Southern Samoyed languages. Of these, one group - the Sel’kup (Söl’kup or Shöl’kup as they call themselves) - also went northward to finally end up living near the mouth of the river Taz. Because of their cultural resemblance with the Ostyaks (Khanty) they were called ‘Ostyak-Samoyeds’ by the Russians.

Live-style and economy

By origin all the Samoyeds were hunters, but changes in their live-style made most of them turn into reindeer herding peoples. Only the Nganasan, living extreme North and isolated, kept up their reindeer hunting live-style even in the 20th century. Other means of economy still had a neolithic hunting-gathering character: they were fishing, they were hunting squirrels and sables in the forests, seals, walruses, ice-bears in the Polar Sea and they gathered different eatable plants and berries on tundra and in taiga. Their main food supply though has always been the meat of reindeer.

At the time of the late 19th century, the time of the first imports of Samoyed dogs, the Nenets and Enets still could be divided in Tundra-Nenets and Tundra-Enets on the one side, and Forest-Nenets and Forest-Enets on the other, having developed dialectical forms of their languages. Nowadays this division remains only within the group of Nenets-speaking peoples.

The Samoyeds had to pay taxes in the form of skins (mostly sable skins, later also squirrel skins) to the Russian Tsar. For paying their tribute to the local tax collector, they had to travel to the nearest town during the annual fairs being held there.

Besides the fact that the skins were used as means for paying taxes, they were also used as commercial trade commodities enabling these people to buy common house-keeping things and tools. The demand for skins was so big that the rich population of sables and squirrels nearly reached the point of extinction in the whole of Siberia.

Marriage and family live

Finding a husband or wife was a complex matter in Samoyed live: bound by rules of exogamy, Samoyed men and women were not allowed to just marry the one they loved. They probably understood inbreeding earlier than anyone in the West or at least they must haven known the consequences by experience. For example, the Enets tribe of Baggo were not allowed to marry with members of the Masodaj, Lodoseda, Bunala, Dekutan, Sado and Sonuko tribes.

They lived in family tribes in tents made of birch-rind, many times covered with reindeer skin in the winter. Differences in possession of numbers of reindeer could be big: ranging from just a few reindeer for poor families to several hundreds or even thousands for rich families.

All the Samoyed peoples had a nomadic life-style, except from those who had lost their reindeer by epidemics of anthrax and therefore were forced to live a more sedentary life near Russian towns and villages. The reindeer being driven northward by raising temperatures in spring, the families had to follow their herd, reaching in summertime the shores of the Arctic Ocean, where they lived hunting seals and walruses. In autumn they returned south, living during the wintertime along the fringe of the taiga. Dependent of the width of the tundra, they sometimes had to travel for several hundreds of kilometres before reaching the shores of the ocean.

War and peace

The Samoyeds were not so peaceful as is generally thought. It is true that alcoholism kept them down, but reports from Nicolaes Witsen in the late 17th century show us that they were involved in wars towards their Russian neighbours and even attacked the town of Pustozersk, located in the delta of the Petchora river.

A poem of a Dutch 18th century Navy officer describes the attack on his vessel which was anchored in the frozen White Sea. These attacks may have been caused by famine in order to get food. Remarkable in the mentioned poet is the description of ‘whistling’ arrows. 20th century anthropological research showed that indeed they were using these types of arrows among other types.

Wars between Samoyedic tribes and other peoples, like the Ostyaks, seem also to have been quite common. Many times the goal here was to obtain the other tribe’s wives. Another reason for tribal warfare was the illegal use of the tundra pastures. The tundra was not common ground, but tribes ‘owned’ their pastures and the boundaries were marked by marking stones.

Disputes among clan members were solved by the head of he clan, sometimes also referred to as the ‘king’.

Much, much more can be said about these peoples, but that would be outside the scope of the article. From here on then we shall turn our attention towards the aboriginal Samoyed dogs.

2. The Samoyed dogs

Introduction

Aboriginal Samoyed dogs do resemble the white Arctic wolf strongly. Of course, depression caused by domestication has altered the morphology from that of the original in the wild living animal, just like it happened to many other domesticated animals like sheep, goats, cows and also the cat.

As Vladimir Beregovoy in his article ‘Primitive Aboriginal Dogs’ has already mentioned in R-PADS Newsletter #1, domestication of the dog took place in Asia about 15.000 years ago. But that of course does not mean that all aboriginal dogs were domesticated at that time.

The determination of the time of the first domestication of the dog is based on findings of animal remains and the results of zooarcheological research.

But to find an answer on the question since when the Samoyed peoples used dogs,

leaving out the question whether they have domesticated the wolf themselves, one cannot base himself on zooarcheological findings, as those findings never could be connected to a certain people. Instead, one has to turn towards linguistics.

From etymology there is no indication that the Uralics knew the dog. Neither is there any indication that the Proto-Finno-Ugrians knew the dog. An etymology for dog appears only in the Proto-Samoyed language, the language that all Samoyed peoples once spoke before they split up in the peoples known today.

As the division of the Uralians into Proto-Finno-Ugrians and Proto-Samoyeds is thought to have taken place about 3000 BC, that must then be seen as being the earliest possible date for the use of dogs by the Proto-Samoyeds.

Where exactly the Proto-Samoyeds started to use dogs is of course not known, but at that time they most probably lived near the sources of the rivers Ob and Yenissei in the neighbourhood of the Sayan Mountains in Southern Siberia. The Proto-Samoyeds being neolithic hunters-gatherers, it is most likely that these dogs served them in helping to catch prey, a task which the dogs in one way or another have kept until recent times.

Due to circumstances not known to us, a part of the Proto-Samoyeds moved northwards leaving the regions in and around the mountains of Central-Asia to finally settle down in the Polar Regions. Probably they were then already speaking different dialects, which would later develop into separate languages. They were the early Nenets, Enets and Nganasan. Their languages are now called the Northern Samoyed languages.

The language of the Sel’kup belongs to the group of Southern Samoyed languages. The Sel’kup people followed the above mentioned three later in moving northward.

Of course, we do not know how the dogs of the Proto-Samoyeds looked like. We do not even know whether they domesticated the wolves themselves, but as all Northern-Samoyeds were using the same type of dog, it may be considered that indeed they domesticated the white wolf during the time they still formed one people.

Such domestication can not have taken place in Northern parts of Siberia as, on arriving there, they were already split up. It may even be considered that an eventual domestication might have taken place from a population of Arctic wolves driven South by the last Ice Age. But these are, of course, all speculations.

Early Western descriptions of exterior and use of dogs

The early travellers were probably not so much interested in the Samoyed dogs they must have seen together with the Samoyed people. Men like the Dutchman Jan Huygen van Linschooten (companion of Willem Barentz during his journey to find a Northern route to India) in the 1590th, the British Peter Mundy, the Dutchman Nicolaes Witsen and the German-Dutch Evert Ysbrandt Ides in the 17th century and later travellers from 18th and early 19th century all described the Samoyed people in their journals without mentioning dogs.

It is first in the last quarter of the 19th century that Western travellers turned their attention towards the looks and use of the Samoyed dog. By that time hundreds of years of contacts with Russians and non-Samoyed peoples had caused a diversion of dog types, at least on the westernmost tundra’s and taiga’s of European Russia. On these stretches, dogs that accompanied the Nenets were not all of them pure white, but could have any colour and be of any type!

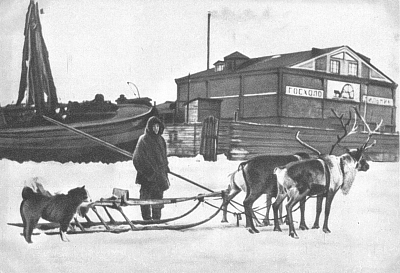

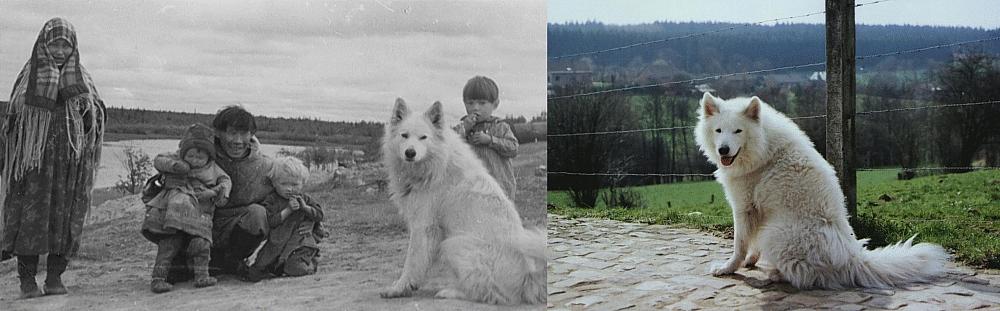

Nenets with mongrel dog at the outskirts of Archangelsk, early 20th century

Descriptions of pure white dogs reaches us from travellers visiting the Bolshezemel’skaya tundra, the biggest tundra in European Russia which stretches from the Petchora river in the west to the Ural mountains in the East, called Arka-ya by the Nenets.

One of these men was the British ornithologist Henry Seebohm from Sheffield. He saw in 1875 the dogs being used for herding:

The Samoyedes proved themselves expert in throwing the lasso. In the left hand they held a small coil of rope, in the right hand the larger half. The lasso was thrown with an underhand fling, and generally successfully over the horns of the animal at the first attempt. The left hand was then pressed close to the side so as to bring the shock of the sudden pulling up of the reindeer at full speed against the thigh. When a reindeer found itself caught, it generally made desperate efforts to escape, but was usually on its haunches gasping for breath in a few seconds. The Samoyede then hauled in the rope, or, if it was nearly out at full length, another Samoyede came up and began to haul it in nearer to the animal. When he was close to it he took hold of the horns, and with a side twist, brought the reindeer down on to the snow. The Russian to whom the fifty reindeer belonged then approached, and taking a thong of three-plait matting from a bunch at his belt, tied one of the animal's forelegs to the hind leg on the same side; crossing the feet, but keeping the legs parallel at the point of ligature.

As soon as the reindeer was left, he made wild efforts to rise and walk; and sometimes succeeded in hobbling a few paces. Finding his strength give way with his frantic efforts to escape, he generally rested with his foreknees on the snow for a time; and finally lay down quietly. A dozen reindeer were soon on the ground. The scene became quite exciting; the reindeer were wheeling round and round in circles. The dogs tied to the sledges barked furiously, and evidently wished to have a share in the sport. The dogs selected by the Samoyedes to help them to get within lasso range of the deer, rushed frantically about at the command of their masters, whose loud cries added to the excitement of the scene. Sometimes a herd of reindeer ran over a place where the snow was unable to bear their weight; and it was interesting to watch them snorting and plunging. As the number caught increased, the difficulty also increased of identifying and catching the remaining few of the fifty that belonged to the Russian, and the Samoyedes with the lassos were driven about in sledges at a rapid pace to get within reach of the animals they wanted. The deer kept together; if one ran out of bounds a dog was sent after it and soon brought it back again. In one respect the reindeer resemble sheep; wherever one goes, the rest try to follow.

In this herd the greater number were females (vah'shinka), with good horns; these they do not cast till they drop their young. A few were males (horre), their new horns just appearing. Those chiefly used in the sledges were cut reindeer (buck), also without horns. Some of the hornless animals leaped right through the lasso and others were caught by the leg.

The lasso is a cord about one hundred feet long, made of two thongs of reindeer skin plaited together, so as to make a round rope three-eighths of an inch in diameter. The noose is formed by passing the cord through a small piece of bone with two holes in it. The lasso passes freely through the hole, while the end is fastened to a little bone peg with a bone-washer to prevent it slipping through the other hole.

The dogs were all white except one, which was quite black. They were stiff-built little animals, somewhat like Pomeranian dogs, with fox-like heads and thick bushy hair; their tails turned up over the back and curled to one side. This similarity between the Pomeranian and Samoyede dogs is a rather curious fact, for Erman mentions a race of people who, he says, resemble the Finns, both in language and features, in a district of Pomerania called Samogitia, inhabited by the Samaites. (Henry Seebohm, Siberia in Europe. London,1880, p. 65-67)

Though not completely misplaced, we shall leave the last remark of Seebohm for what it is, as an historical explanation of it would bring us far outside the scope of this article. With regard to the Samoyed dogs on the European tundra’s, the existence of white dogs only on the Bolshezemel’skaya tundra, is confirmed by L.S. Berg, President of the All-Union Geographical Society of the U.S.S.R. somewhere in the first half of the 20th century.

The situation on the Siberian tundra’s differed from the European tundra’s: from the Yamal Peninsula in the West to the Taimyr Peninsula east of the mouth of the Yenissei river, white dogs could be found. Here it must be mentioned that the white aboriginal Samoyed dogs were not only used by the Samoyeds but also by the Reindeer-Khanty, whose summer pastures reached as far north as the Southern part of the Yamal Peninsula. In the East, some Dolgan tribes – neighbour to the Nganasan-Samoyeds - used to have white dogs as well.

The Russian anthropologist A. A. Popov researched the Nganasan-Samoyeds in the 1930’s. On their dogs he writes:

“Reindeer herd dogs are a great help in gathering the herd and in catching individual domesticated reindeer. They are a breed of short-legged, Arctic, white dogs [known elsewhere as ‘Samoyed’ dogs] which somewhat resemble polar foxes. All a herdsman has to do is give a shout, and the dogs will drive all the scattered reindeer to one spot at once. The Nganasan supply their neighbours, the Dolgan and the northern Yakut, with herd dogs, and they fetch high prices. These dogs are usually kept tied inside the tent or to a sledge with adjustable blocks”

(A. Popov, The Nganasan, The Hague, 1966. p.76)

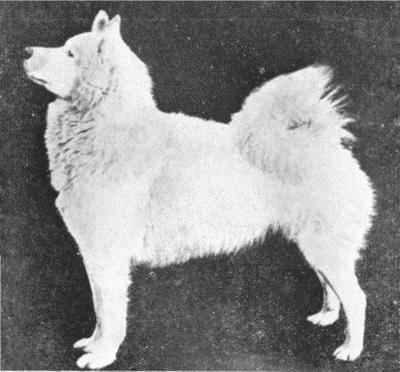

Reindeer herd dog from Nganasan Samoyeds

from A.A. Popov, The Nganasan, Moscow, 1948. (Original Russian Edition)

The dogs are tied on each sides of the entrance and behind the hearth. In cold weather they are not let out of the tent at all. They put the puppies, which are allowed to walk on the beds during the day, into a bag at night, so that they will not disturb people’s sleep. In the morning, they shake the bag and let the puppies out. (ibid. p. 96)

The Nganasan had an economy based on both the herding of domesticated reindeer and the hunting of wild ones. He describes the use of dogs in helping to catch wild reindeer:

“Certain types of collective hunting which had in the not too distant past great economic significance, and have been preserved until our times among the Nganasan, are of great interest. These are the slaughter and penning of wild reindeer in nets.

‘Flags’(labaka) used to be indispensable appurtenances of summer stalking of wild reindeer. They were long stripes of skin, decorated with black, or else white fans of partridge wings, hung on the ends of long sticks.

Hunters following a herd of wild reindeer would plant the flags in the form of two diverging rows, leaving between them a space of 4 to 6 metres. ‘Signalers’ (seriti) would hide near one row of flags, at the wide end of the lane.

The cleverest hunter, driving a sledge drawn by two domesticated reindeer, would drive a herd of wild reindeer into the lane. The signalers then would spring up, crying out and waving garments about, thus driving the reindeer further. At the narrow end of the lane the reindeer would be met by the arrows of two or three hunters armed with bows. The flags served as a sort of hedge keeping the reindeer from running aside. This method of hunting was called ‘ngatangiru’. If the reindeer were near a lake, then the flags were planted in a single row. Opposite from this line, at some distance of it, people would station themselves in place of the second row of flags. Then the reindeer would be driven into the water by dogs along the lane thus formed. Then the hunters on the other side of the lake would at once go out in their canoes to kill the wild reindeer with long shafted spears. This method of hunting was called ‘suodisiti bantanu’.

The two methods of hunting described were used most often in the summer, at the time of the molting of the geese, by several hunters working together. For example, the slaughter might be accomplished by three or even two hunters. As one of them patrolled the lake, the other, aided by dogs, which are greatly feared by wild reindeer, would drive the wild reindeer into the water. When the reindeer reached the lake, the second hunter would quickly go out in his canoe and kill them with a spear.” (ibid. p. 35)

We can clearly see that for hunting wild reindeer in fact no specific hunting qualities were required. On the contrary, in the hunt on wild reindeer, people made use of the herding and driving qualities of the dogs! Such driving qualities were also needed for the hunt for geese:

“When there are only a few geese on hand, they are driven and hunted down by dogs along a lake or river bank. Using this method, several men with dogs lie around a lake on which there are geese. One or two hunters go about the lake in canoes and drive the geese to the bank. (…………). When the geese come out onto the bank, the hunters which are lying in wait for them hunt them down with dogs. Usually such hunting does not produce great results, since some of the geese almost always get away.” (ibid. p. 47)

Dogs were also used during the summer migrations:

“During the summer migrations, a man well acquainted with the region will walk, with his staff in his hand, at the head of the caravan. He is followed by several men on foot with dogs who drive the herds of freely roaming reindeer. ……..” (ibid. p. 102)

The first imports

It is probably thanks to the English captain Joseph Wiggins that the first all-white dogs came to Europe. Joseph Wiggins was a ships captain who, after a career on the commercial ocean-going trade, decided to return to the old dream of his youth: the exploration of the northern sea-route. His goal was to find a route for commercial trade with Siberia, which was rich with minerals. Altogether he made in the period 1875-1895 six expeditions, which led him to the Yenissei river and even as far upstream as the town of Yenisseisk in Southern Siberia. He seems to have taken several dogs with him on his returns to England. Unfortunately there is no documentation on these imports.

A British timber merchant, E. Kilburn Scott, being on business trip to Archangelsk, bought a puppy as a present for his wife from Samoyeds living not far from that town. This dog, named Sabarka, was not at all white but brown with white at feet and tail. Another recorded import, Whitey Petchora, was also not pure white. The first known pure white dog was taken home late 1893 by Francis Leybourne Popham. Travelling with his own ship to Siberia in a convoy of other ships under the command of captain Joseph Wiggins, he bought a pure white dog from Tundra-Enets living at Golchika. A picture of this dog is abusively named “imported 1894 ……”

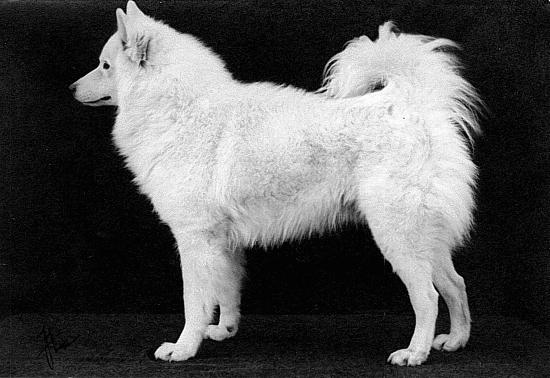

Musti, imported November 1893 from Golchika, Siberia

Thanks to personal connections of captain Joseph Wiggins - friendships made during his travels - it was possible for both the Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen and the British explorer Frederick George Jackson in the 1890th to obtain dogs from Siberia for their expeditions. Dogs could be obtained from a dog merchant who bought them at the village of Beresowa during the annual fair. Of the dogs bought, most of them were pure white, but as Nansen complained, some of them were castrated. As the Khanty had the habit of leading the pulling rope of there sledges underneath the belly of the dogs and as this caused damage and infections on the testicles of the male dogs, and as these males were for that reason castrated, it might be presumed that the castrated dogs which the explorers had bought were of Khanty origin.

Some of the dogs G.F. Jackson used on his expedition have been brought home to England and formed, among other imported dogs, the start of the worldwide population of Samoyed dogs.

Three other famous imports were the dogs Antarctic Buck, Houdin and Ayesha. Houdin was presented to or bought by E. Kilburn Scott from the Duke of Abruzzi, commander of the Italian North Polar Expedition.

Antarctic Buck, offspring from dogs taken to Antarctica by the Borchgrevink expedition and obtained in Australia by Mr. and Mrs. Kilburn Scott.

Houdin, from the Italian North Polar Expedition and brought to England

Ayesha was taken to Archangelsk from Novaya Zemlya by Nenets. She was pure white, though there must be doubts as to whether she was of a pure aboriginal Samoyed bloodline, as in the late 90’s of the 19th century the governor of the province of Archangelsk, Alexander Platonovich Engelhardt, had ordered to send each year mongrel dogs from Archangelsk to Novaya Zemlya to keep up the number of dogs living there. Dogs at Novaya Zemlya lived a short live due to fights, diseases and harsh circumstances, but they were of economic importance for the Samoyeds living there because dogs were used to haul their sledges in the absence of reindeer on these islands.

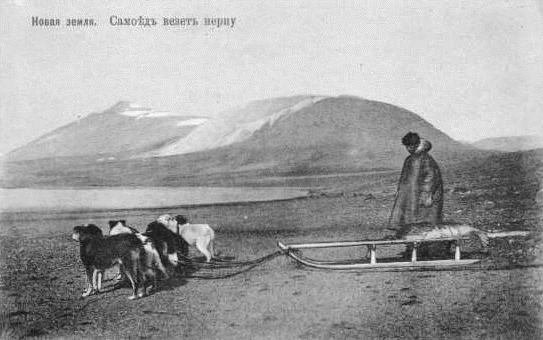

Samoyed man with dogs and sledge, carrying a seal at Novaya Zemlya. Early 20th century

Of Ayesha exist only a few vague pictures. One of them is presented here:

The world population of Samoyed dogs can therefore be seen as having been derived from only a handful of imported aboriginal Samoyed dogs. What that meant and what it led to, can be read in Part II of this article.

Lobi, probably one of the last imports

Part II: A short history of the Samoyed dog as

a registered breed (by Sarah de Monchy © 2005)

Introduction

This part is written in an attempt to analyse why and how the registered breeding of the Samoyed resulted in a breed known with this name, but which - in varying degrees of deviation – has now hardly more in common with the aboriginal Samoyed than the white colour of its coat.

The first section ‘Registered breeding’ describes this development. The following section ‘Short history of the Dutch breeding of Samoyeds’ sketches the only known exception to this worldwide trend, as in Holland a small group of breeders still tries to keep on breeding to the aboriginal type.

The last section ‘Cynology and the preservation of cultural heritage’ discusses aspects of the environment in which registered breeding takes place and how it, nonetheless, offers a solution for preserving the breed for the future.

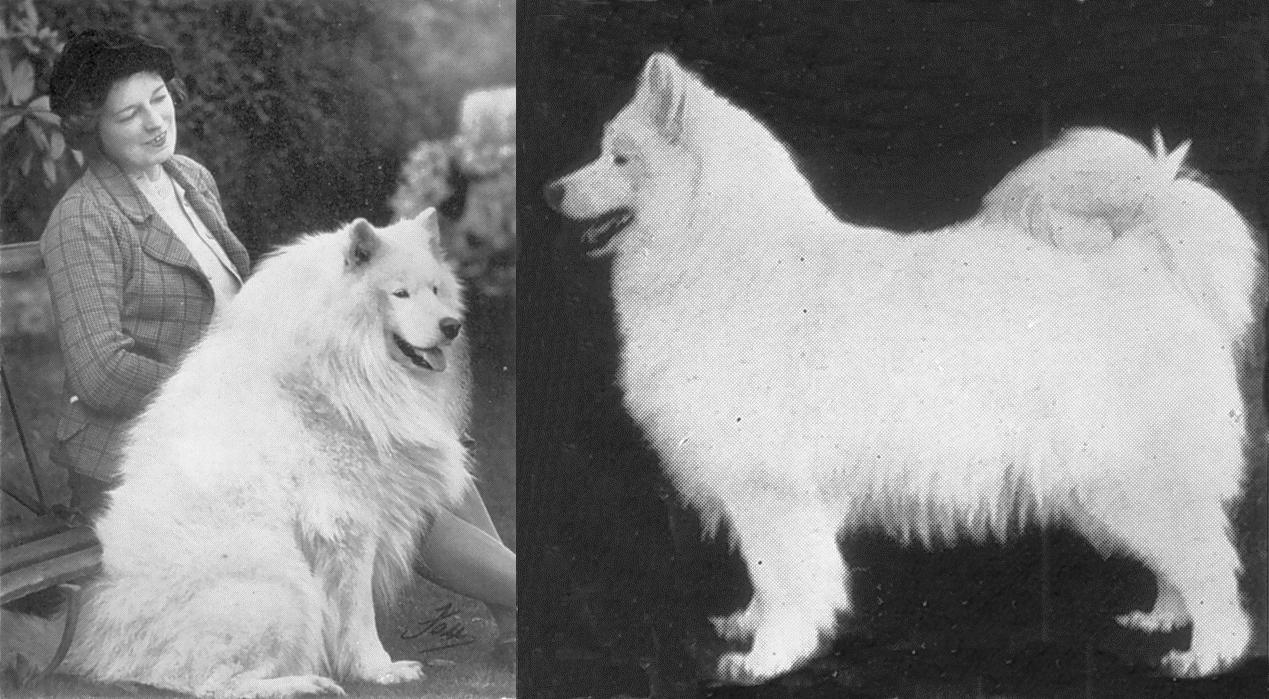

Noho, aboriginal Samoyed on Yamal, 1962 and Na-Njarka, bred in Holland in 1996, both dogs are at the age of two years

Polar Light of Farningham, bred in England around 1920, and an ancestor of Na-Njarka, here in 2002 at the age of five years

Registered breeding

Ernest Kilburn Scott and his wife Clara were the first to take up the systematic and purposive breeding of the Samoyed dog in the Western world, embarking on a project of many, many years to come. Growing up with these dogs, their daughters Joyce and Ivy would become actively engaged in this project too. It all started with the business trip Ernest Kilburn Scott made to Archangelsk in 1893, staying there for a couple of months, and, as mentioned before, the acquisition of the pup Sabarka when visiting one day a Samoyed tribe living nearby town. He never travelled all the way into Siberia, but via many contacts maintained he did manage to gather information on the dogs originating from those territories. It resulted in the building-up of the famous and large scale breeding kennels ‘of Farningham’. A name they took for their kennels after moving to Farningham, Kent, in 1922. Till that time no specific kennel name was used.

Sabarka was used for siring the very first litter bred off an imported bitch called Whitey Petchora and is still to be found in the pedigree of Samoyeds today. Soon after more dogs came into reach, like Musti of which another litter with the same bitch was bred. Besides the directly imported dogs, the acquired ones that were among the few canine survivors of different Polar expeditions played the most significant role in their breeding program. It has been the great merit of the Kilburn Scott’s that when typical examples came within reach, they put a great effort in acquiring these dogs for their kennels. Antarctic Buck, for example, an offspring of dogs taken by the Borghrevink expedition to Antarctica and on returning from the South were left behind in Australia, was put on display in the zoo in Sidney. There he was seen by Mr. and Mrs. Kilburn Scott when visiting Australia in 1904. A year later they managed to obtain this dog and had him shipped to England. Unfortunately, not long after he died of distemper, but by then he had sired at least two litters, which secured his contribution to the breed.

That a Samoyed dog ever reached the very South Pole is a tall story. Because of an outbreak of distemper on Greenland at the end of 19th century Denmark forbid the export of dogs from its colony. After the turn of the century that situation had changed though. When Amundsen started to prepare for the South Pole in 1910, he paid a visit to Copenhagen ordering 100 Greenland huskies, which he managed to secure through the Danish government. When the ‘Fram’ left Norway in 1911 sailing for the South she had 97 dogs on board being the ones delivered from Greenland. Amundsen apparently did use Samoyed dogs for sledding though, but that was on his next expedition of 1917 to 1920 for the North East passage sailing along the coast of Siberia to the Street of Bering ending up in Nome, Alaska.

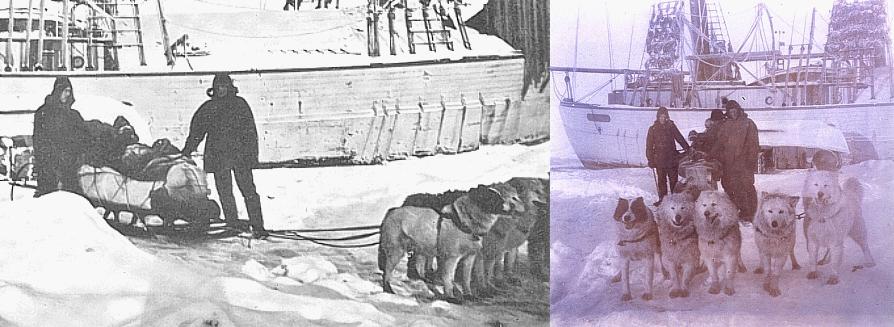

Stops were made at Waigatz and Dickson Island where some dogs were taken on board. Further on the way his ship ‘Maud’ was brought up by ice and had to spend the winter beset on the Siberian coast at Cape Chelyuskin. There exist two pictures of the same situation and taken from different ankles, showing a sledge with five attached dogs in front of Maud. These were taken on the 20th October 1919 at Cape Chelyuskin, when Amundsen sent a party of three of his crewmembers with post to Nishny Kolymsk, a town 200 miles land inwards. The three dogs in the middle are unmistakably of Samoyed origin. The one on the left with black plates on the head and short coat reminds on the dog Luska (see: www.oldsams.info), owned by the Prince of Wales in the eighties of the19th century. The dog on the right is clearly a full size bigger than the others and his sturdy posture is more like that of a Greenland husky male.

Pictures taken on 20th October 1919 at Cape Chelyuskin

In 1909 Ernest Kilburn Scott formed the Samoyede Club, being the first of all special Samoyed breed clubs established in Great Britain as well as in the whole world. This club adopted in May 1909 the first breeding standard, drawn up by the Kilburn Scott’s (probably by Clara, who was the actual breeder of the couple). The ‘Summary of points’ opens with the paragraph: “Colour. Pure white; white, with slight lemon markings; brown and white; black and white. The pure white dogs came from the farthest north, and are most typical of the breed.” The second sentence proves, that the assumption was held that they were dealing with an existing, distinguishable white coloured breed. It also reveals to us the apparent awareness that some of the dogs used for building up the breeding population, showed aberrations to the typical appearance of that breed indicating a certain degree of contamination with other breeds.

The Kilburn Scott’s must have themselves begotten an image of the looks of the purebred dog, which served as a guideline for where to aim for, and how to act, and how to proceed in the selection process. The first four paragraphs of a promotion leaflet of the Farningham kennels read as follows:

“These kennels were the first to be established, and for over thirty years Mrs. Kilburn Scott has been most careful to breed and import only correct types of Samoyed dogs.

They are the domesticated dogs of the Samoyed people and their natural habitat is the Tundra country which stretches form the White Sea in North Russia to the Yenesi River in West Siberia.

USES. The Samoyed people use them principally for driving and rounding up reindeer, a task similar to that of droving sheep, and they have been so engaged from prehistoric times, also they are used for hunting.

They have hauled sledges on various Arctic and Antarctic expeditions and many of those at Farningham are directly descended from such dogs.”

Due to the diversity in origin of the few - actually very limited number of - dogs available for the breeding process, it was possible for them to keep eight different bloodlines in their kennels upon a certain stage. Among the dogs they had bred they distinguished three different types of head, which they called: the bear type, the fox type and the wolf type.

By experimenting and consistent breeding they managed to create a viable and pure inheriting population of the type they wanted. It is without question that the Kilburn Scott’s are accountable for establishing the Samoyed dog in the Western World as a recognised and registered breed. Instead of trying to create a new breed of their own, which in fact would have been a much easier goal to accomplish, the goal they set themselves was to stick as close as possible to the aboriginal type. Their eventual idea of breeding Samoyeds to provide Polar expedition with dogs, turned out to be in vain, and the sole purpose of breeding became the showring for the Kilburn Scott’s too. But this did not change their judging of the breed, as they have always kept looking for an overall sound exterior.

In the early days of Polar expeditions it was common to invite returned Polar travellers to lecture about their adventures for a select audience. But the race to reach both the North and the South Pole turned public interest in Polar expeditions into a complete hype, reflected by articles published in newspapers. Everything connected became interesting for quiet a while. Publications on the Arctic became so popular that several books were translated and published in foreign languages reaching an even broader audience. It also stimulated the wish to own a dog connected with these heroic adventures. Together with the steadily growing attention for the breed, the number of people engaged in breeding augmented. In the first two decennia of the 20th century the Samoyed dog was nationally and internationally sought after and British kennels exported to countries all over the world. World War I implied an interlude to international cynologic live and in England it was even officially forbidden for a while to organise dog shows. After the end of World War I cynologic live revived and soon flourished more than ever.

With the outbreak of the Russian Revolution it became as good as impossible to import dogs to Western Europe from regions under control of the new regime. Because when Bolsheviks took over a region, it was closed to outsiders. So the trade route between the West and Siberia had to close down. A route which had served as a gateway for obtaining typical specimen of the aboriginal type.

It was during the twenties that in England the transformation process began, changing step-by-step the functional exterior of a working dog into that of a show dog with many dysfunctional characteristics. Until this period the breeding by the Kilburn Scott’s had been leading, but from then on other kennels started to dominate. The best well known was to become the ‘Arctic’ kennel of Miss M. Keyte-Perry who succeeded over the years in gaining in the show ring an enormous collection of champion titles.

Pictures from the thirties of winning dogs on shows in England clearly show that the trend towards big-boniness, impressiveness and exuberant coat had already got going.

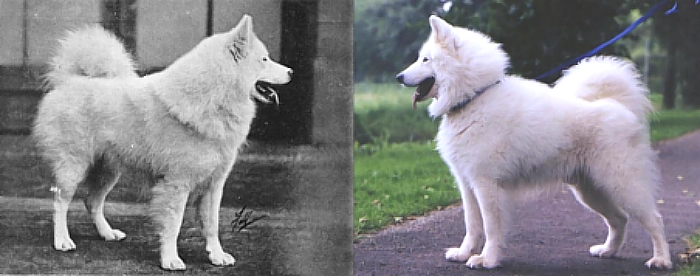

Title winners on shows in England in 1938: Spartan of the Arctic and Crystal of the Arctic

With the following typical characteristics the tendency to exaggerate proceeds further and further: the whole appearance of the dogs becomes increasingly plump and squat, low on legs, with steep hindquarters, small round feet, the overall coat profuse and long, the muzzle short, broad and with a set of teeth of underdeveloped size, the ears small, flabby and little mobile, a domed skull, pronounced stop, and big round eyes placed towards the front of the skull making the sight ankle smaller thus giving a narrowed sight field.

Another peculiarity of the changed type is the rapid pace in which the development of the body reaches the state of fully blossoming adulthood. At the age of two, these dogs are at their top, from whereon they start to look aged very quickly. By contrast, dogs of the Farningham type develop slowly: a bitch is not fully outgrown before she turns three years old and a male reaches its top at the age of five, both keeping their vitality and beauty till a very old age.

It is very well possible that crossbreeding has occurred with other breeds to achieve this transformation. It is a public secret that in England (in the fifties?) at least once a Chow Chow has been used for inbreeding. It is quite possible that the White Keeshond has been bred in as well. It is known that in the thirties and forties it occurred on shows held in Holland and Switzerland that specimen of the White Keeshond were subscribed as Samoyed and had to be removed from the ring at the start of judging. Also the silhouette of many today’s show Samoyeds fits the silhouette of the Keeshond. Anyway, a lot of the above mentioned characteristics are traits adherent to either of these two breeds and strange to a sound working dog.

At the end of the fifties the pure Farningham type is no longer to be found in the prominent breeding kennels of England. Around that time, R-PADS member Mr. Clay met on an occasion Mrs. D.L. Perry, owner of the Kobe kennels. They discussed the breeding in England and she admitted to him in private that a breeder who wanted to compete successfully in the showring, had been forced to follow this trend as with dogs of the Farningham type one did not stand a chance anymore. Step by step the Samoyed breed has worldwide undergone in less than a hundred years a metamorphosis in which the wolfishness so typical for a Polar dog, has been bred out. Together disappeared the functional construction of the body that goes along with speed, stamina and nimbleness, necessary to work under all conditions as herding, hunting and sledge dog.

Todays Samoyed bred for the show

However, apart from all the other changes in appearance it is the change in expression of the head, which is most striking. In the above mentioned leaflet of the Farningham kennels the following description of the head is given:

“The ears are erect, slightly rounded at the tips and set well apart, giving a fine open forehead, which indicates the extremely intelligent expression of the breed.”

Exactly this facial expression has been swapped for the looks of a teddy bear, the domed forehead concealed by thick white hair like a knitted cap slid down to the eyebrows with on top two little triangles being the tiny ears popping up.

On July 22,1997 the FCI published the latest revision of the standard. In this version a remarkable sentence is added to the paragraph ‘Behaviour and temperament’, stating: “The hunting instinct is very slight.” It shows that the transformation process continues, touching now other undesirable traits for passionately hunting behaviour is inconvenient when keeping a dog as family pet. But the past still lingers in the description of the general appearance, which opens with the words:

“Medium in size, elegant, a white Arctic Spitz.”

Short history of the Dutch breeding of Samoyeds

The breeding of the Samoyed in The Netherlands starts with the import in 1924 of the bitch Mooswa of Farningham and the male Ikon of Farningham, later registered in Holland as Farningham Ikon of Samoya and who would become the founder of Dutch bloodlines. The name Samoya refers to the name of the first Samoyed kennel in Holland where in 1926 the first litter is born bred of these two first ones. More imports followed of which most came from the Farningham kennels. In 1932 the Dutch Samoyed Club was established. One year later, this name was changed into Polar Dog Club to shelter one Siberian husky as well, but in 1963 it was renamed with its former name, from then on solely occupying itself with the Samoyed breed. During the thirties the club flourished and breeding was done at a large scale – 24 different kennel names are to be counted in connection with this period. The influence of the stud Ikon got firmly rooted in the Dutch population: from 1926 up to 1936 he sired 21 litters producing 123 offsprings.

Up to World War II close contacts were maintained between Dutch breeders and the family Kilburn Scott. Mrs. Clara Kilburn Scott and her daughters Joyce and Ivy were all renowned judges and were several times invited over to the United States and the Continent for judging on shows. The last time one of them judged in Holland was in 1939 when Joyce did the judging on the yearly held match of the Polar Dog Club.

The outbreak of the war caused a rupture in the building-up of the population. With 26 litters registered in 1936, breeding had reached its top and diminished thereafter rapidly. It’s true that in the forties, during the years of war as well as after, almost every year multiple litters were bred, but in the fifties during the post-war reconstruction of The Netherlands breeding nearly came at a standstill. On average only one litter per year was born and in the years 1954 and 1956 even nil. In those days of overall scarcity people had to work very hard just to make a living and having a purebred dog was the last thing that mattered. As long as this economic climate lasted it appeared to be utterly problematic to find good homes for the few puppies bred and to find new homes when needed for mature ones.

The Dutch share of the Farningham heritage owes a lot to the way Mr. Wim M. Clay dedicated himself to help to prevent its complete loss during this difficult time. By coincidence he got in touch with the breed in 1946 and getting subsequently more and more involved with the breed, he became acquainted with breeders and judges who had been engaged with the breed from early years on. These people, knowing all about the Dutch breeding, passed him on their knowledge and asked him to become judge of the breed, which he did in 1955 and since then still is. Up till today he has kept the promise made to them to take care of this cynologic legacy. Rowing against the tide, he has never given up to stimulate and advocate the preservation of the Farningham type when and wherever he could.

As a judge and breed specialist he has heavily contributed to the continuation in Dutch showrings of a climate vital to breeders committed to keeping the Farningham type in existence. With an experience of almost fifty years actively judging he is still welcoming anyone who wants to be taught when trying to become judge of the breed.

He actually never bred a litter himself but was involved in different ways with several. Holding the position of chairman of the Polar Dog Club from 1956 to 1962 he went to great lengths stimulating and supporting the breeding of a couple of litters which turned out to be crucial for later years.

To augment the number of dogs left available for breeding, two female pups were imported in 1955 from Finland and a male pup from England in 1957. All these imports appeared to be unsatisfactory when developing into adulthood, and time was running out for saving the Farningham heritage. The opportunity to try the option of inbreeding emerged when the retired Queen of Holland, Princess Wilhelmina, asked the Polar Dog Club to provide a stud to sire a bitch she received as present when visiting Norway. This bitch, called Ibur Stella, was unrelated to the Dutch population and although big of good type. Clay proposed the dog Bertil, and in September 1958 a litter of 4 bitches was born, which turned out to be so satisfactory that the same combination was made again, producing in June 1960 a second litter with 4 males and 3 females. In 1961, Sunna van het Aardhuis - a bitch of the first litter - was subsequently mated with her father resulting in September into a litter of 4 males and 2 females. With this deliberate inbreeding, the Farningham type got firmly rooted in their offspring. All together a tiny but viable pool of breeding stock was so recreated, through which this type could survive in Holland.

Bertil, born in 1950, at the age of eight years

Most certainly in the sixties and very long after England was internationally seen as the Eldorado of dog breeding. This is why the prominent breeding of that country, with its transformed type bred for shows, was perceived as leading throughout the world. In all countries where breeding was not yet heavily influenced by the English show trend, sooner or later a next generation of breeders started to follow this trend to an increasing extent, so taking over or dominating the existing breeding practice and culture.

In Holland too, a slowly growing amount of fanciers of the show type was to be found who - with the purpose in mind to alter their breeding in that direction - started to import dogs at the end of the sixties and/or travelled with their bitches across the border to have them sired. Up to the nineties they formed a steady growing minority within the Dutch Samoyed Club. About half of the Samoyed population present today in the Netherlands, consists of their breeding products. Next to the two sides of the show dog fanciers and the working dog fanciers, a group came into being in the eighties that was in between and mixed the show and the Farningham type.

Apart from the fraction of show type lovers, the overall breeding continued for two decades with hardly any further influx of imported genes. As economy started to flourish in the second half of the sixties the total population grew steadily with different breeding lines emerging from what had been saved. But as these lines were all very close related an unintended high degree of inbreeding took place and problems not seen before started to surface in the eighties. Particularly now and than occurring hip dysplacia urged breeders of the Farningham type to make outcrosses. They were and are faced with a difficult balancing between maintaining health and the risk of importing other inheritable diseases new to their breeding lines.

They are also confronted with the issue how to lose not too much of the typical appearance, of which the wolfish head appears to be touched at first. In the search for healthy inheriting studs with an appearance not deviating too much, contacts within the community of the European sledding sport appeared to be an important gateway. Dogs selected for siring were found in Germany and Switzerland where mushers in the pursuit of a sound working sledding team had based their breeding in the seventies and eighties on imports from Holland stemming from the Farningham bloodlines.

In other European countries the appearance of the breed from the first decades has by now – at least at shows - totally vanished. Today only in the Netherlands it is still possible to subscribe a dog of the pure working type at sufficient different judges to be able to earn the champion’s title at all. Two decades ago such a dog could still win international champion titles by attending shows in neighbouring countries. The fact that the Farningham type has held for such a long time a dominant position in Holland has possibly something to do with the popularity of the breed in the thirties. Relatively many (people) experienced a Samoyed during their childhood days and were left with precious memories. As an adult when attaining the position that they can afford to buy a dog, they went searching for one with the familiar looks from their youth. This generation of dog owners is by now getting to old to keep a dog. Now the Farningham type is favoured by a new generation of owners who are simply attracted to a dog with natural looks or want to compete in the sledding sport with a purebred Samoyed.

Left: Ivy Kilburn Scott with Samoyeds in sledge, ca. 1920.

Right: Sjaak van den Ham racing with team bred by his wife, European championship contests of the World Sled dog Association, 1999.

The irony is that although the Samoyed is not a sled dog by origin, the use for this goal - today in the sledding sport - seems to have to play once again a vital role in the preservation of the breed outside its home country. People that want to be successful in this sport are in need of a physically well-functioning dog. And, as it turns out, the selection process that comes along a breeding program opting for dogs fit for this sport automatically generates a certain degree of backbreeding to the aboriginal type. The hunting instinct of these dogs is clearly fully intact, as well as the tendency to use a penetrating high pitched barking when calling or inciting action. Whether this applies to the preservation of all typical mental capabilities of the breed raises a big question mark, as the sport practice is incomparable to the original working practice of herding. To find answers, it’s obvious we should consult the experts on this matter. Fortunately, this is now possible again, but just like a century ago it is still very complicated for someone from the Western world and not knowing the Russian language, to make contact with Nenets people, so any help would be most welcome.

On cynology and preservation of cultural heritage

Presumably Holland is today the only country where still a few kennels are to be found continuously and consistently breeding in accordance with the views held by the Kilburn Scott’s. Who, in the times the registered breeding started from imports out of Siberia, chose on their turn to aim for breeding to the aboriginal type. It is also the only country, where still a small flock of judges exists, acquainted with an appearance of the breed which in the rest of the world has sunken into obscurity or more often: is totally unknown. Although pressed into a minority position they stick to the views of the early days of Dutch cynology that the appearance of a breed is something of cultural significance and for that reason worth to preserve for the future. Dogs like the portrayed Na-Njarka stem from a population resulting from this tradition.

Not just a part of the cultural heritage of registered dog breeding has so been preserved. As these dogs of registered breeding belong to the cultural heritage of North West Siberia and especially to the culture of the Nenets people. This explains the amazing fact that a dog born in the Netherlands in 1996 out of ancestors imported about one hundred years ago shows such a remarkable resemblance to Noho, the aboriginal Samoyed that Vladimir Beregovoy bought in 1962 from a Nenets family on the Yamal peninsula. It also explains the amazement among a delegation of Nenets invited over to Holland in October 2001 to attend an intensive eight days conference program arranged by Arctic Peoples Alert, a Dutch organisation supporting indigenous peoples in Arctic and Sub-Arctic regions. Part of the program was a discussion meeting open to public on which R-PADS member Mrs. Bartol managed to show them pictures of Samoyed dogs she breeds. Seeing these pictures caused a stir among the elderly people of the delegation. They confirmed to recognise the dogs as being the same as theirs, but then switched from Russian to their own language talking excitedly to each other. What they were saying had to remain unknown, as the Nenets language went beyond the capabilities of the student of Russian language acting as translator.

Left: group of first generation breeding of imports + offspring. England, ca. 1905.

Right: Alie Bartol with 4 generations of her breeding. Holland, 1998.

The very possibility that these Nenets could find in Holland dogs with the looks of the breed that is now vanishing in their home country, has been enabled by the formation of internationally organised cynology. A phenomenon emerging during the second part of the 19th century. First limited to a very thin top layer of society, it started as a hobby of people sharing a great interest in dog breeds. These people were accustomed to travelling abroad, maintaining internationally contacts as an aspect of their way of life. So, it is not surprisingly coincidental that the first kennel clubs were founded in different countries about the same time and opinions held will not have differed much. Dog breeds were seen as a cultural heritage of the past and so it came to be that in 1890 the Dutch Kennel-club Cynophilia was established with the objective to preserve and to improve dog breeds.

From the start on, the event of the year for all kennel clubs became the organisation of annual dog shows with the purpose to display the looks of fine specimen of all kinds of breeds, and rare breeds were of special interest. The next step has been to compete for which dog was best looking. Testing and proofing of working capacities was done in a different setting, like for instance in field trials held by hunting clubs who preferred to restrict these occasions to a highly exclusive circle of people. Shows on the other hand were open to the public, attracting through the years bigger and bigger crowds of dog fanciers coming from all layers of society. This phenomenon has grown into a worldwide institute covering all kinds of dog breeds with standards, societies, breed specific clubs, registration of pedigrees, stud books, judges, a show industry, etc. etc. On the one hand it has meant that when a breed got officially recognised, it was subsequently saved from vanishing, caused either by extinction, or dissolution beyond the point of distinction due to mixing with other breeds. On the other hand it developed in such a way that official cynology now undermines the preservation of many a breed. In the course of time exhibitions developed into an everything dominating show business with dynamics all of its own. And it was here that its second goal - to improve breeds – was twisted and exaggerated to an extent that it made cynology going off the rails.

Unfortunately, the history of the Samoyed breed illustrates very clearly how these dynamics work and the disastrous influence competing at shows can have on the exterior of a breed. When dogs were judged in the showring the relation to the working practice faded further and further into the background and everything was going to be revolving around the word ‘beauty’. What was understood as such reflected the taste of the day and the opinions held on beauty in the country concerned.

At the same time qualifications received at shows were going to matter more and more, particularly to breeders. This mechanism was boosted by the strong competition element intrinsic to shows. Because of this, for many a breeder and owner the earning of personal honour and glory in the show ring became the focus point of attention. Besides, reaching the status of breeder of champions brought along very tempting financial aspects like a prominent position on the puppy market and a high fee for the services of a stud.

All together, it stimulated kennels to improve their breeding towards the creation of an ever more beautiful appearance, following fashionable trends defining what to pursue and so augmenting their chances to win at shows.

This all results into a situation that is exactly opposed to the kind of situation enabling the preservation of a breed for the future. As every experienced breeder will tell, to keep on breeding outstanding dogs, generation after generation, is the most difficult thing to accomplish. To be able to do so, one is dependent on the breeding by others. It also requires a steady flow of information accessible to everyone interested, an open exchange of information, uninhibited recording of problems arising and a working together. Because what matters ultimately, is the overall quality and size of the population. And that is a shared responsibility of everybody involved: breeders, judges and owners.

Unfortunately, these conditions are incompatible with a highly competitive environment. So the second goal formulated at the on-set of organised cynology – to improve recognized breeds – became a euphemism for to change and appears to be at odds with the first goal: to preserve dog breeds for the future as a cultural heritage of the past.

However, the Dutch history of the Samoyed shows the other side of the coin. It proves that organised cynology does have the potential to preserve a breed. To reinforce this potential the relation with the working practice needs to be restored in a well-defined and correct way.

What Japan recently did - reclaiming the Akita Inu as a part of their culture and national pride - sets an example. They redefined the breeding standard, so causing a split-up into two different breeds – the Akita Inu and the Great Japanese dog. Worldwide, dogs were allocated to either of the breeds depending on how much they deviated from the standard drawn up by Japan.

Today’s FCI-standard of the Samoyed mentions ”Utilization: sledge- and companion dog”. If Nenets people would make the step to approach the FCI claiming the aboriginal Samoyed as their cultural heritage, an official split-up in the Aboriginal Samoyed as working dog and the (transformed) Samoyed as companion dog could possibly be brought about. For the building-up of a registered population of Aboriginal Samoyeds would automatically imply the opening of breeding registers. And that would provide the opportunity to unite all dogs of aboriginal type – those outside Siberia of registered breeding and those unregistered still alive in their home country – into one worldwide population large enough to be truly viable, creating a chance for both to be preserved.

I‘m fully aware of the fact, that to the Nenets the preservation of the canine part of their cultural heritage will not be on top of the list of priorities, as this Arctic people has far more serious problems to deal with. However, with combined forces we might succeed.